- Home

- Jeremy P. Bushnell

The Weirdness

The Weirdness Read online

THE WEIRDNESS

Copyright © 2014 by Jeremy P. Bushnell

First Melville House printing: March 2014

Melville House Publishing

145 Plymouth Street

Brooklyn, NY 11201

and

8 Blackstock Mews

Islington

London N4 2BT

mhpbooks.com facebook.com/mhpbooks @melvillehouse

Library of Congress

Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Bushnell, Jeremy P.

The weirdness : a novel / Jeremy P. Bushnell. — First Edition.

pages cm.

ISBN 978-1-61219-315-1 (pbk.)

ISBN 978-1-61219-316-8 (ebk.)

I. Title.

PS3602.U8435W45 2014

813’.6—dc23

2013041263

v3.1

To Atwood’s Redraft, for everything

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Chapter One: The Fundamental Weirdness

Chapter Two: Touched In the Head

Chapter Three: Profoundly Sucking

Chapter Four: Waving Goodbye Forever

Chapter Five: Failure of Imagination

Chapter Six: Listen, Audience

Chapter Seven: Douchebags

Chapter Eight: Third-Guessing

Chapter Nine: The Loosening

Chapter Ten: Away

Chapter Eleven: Social Animals

Chapter Twelve: Back to Work

Chapter Thirteen: Killing Machines

Chapter Fourteen: Ridgeway Vs. Cirrus

Chapter Fifteen: Deus Ex Machina

Chapter Sixteen: Full Disclosure

About the Author

Reading Group Guide for The Weirdness

CHAPTER ONE

THE FUNDAMENTAL WEIRDNESS

BANANAS AND CIGARETTES • 80,000 YEARS OF COMMERCE • PEOPLE HAVE PETS • WHAT ELECTRONIC MUSIC CONFERENCES MIGHT BE LIKE • PLACES NOT TO HAVE SEX • NICE EVENINGS • FUCK THE PAST TENSE • THE WORLD IS A RIDE • REALLY GOOD COFFEE • THE LIGHTBRINGER

Billy Ridgeway walks into a bar with a banana in his hand.

It’s November, and gloom has settled over Brooklyn, but this bar generates its own warmth, running forced heat over a narrow room crammed full of humans. A clientele mashed into intimate proximity by shared need, if not exactly by fellow feeling. They drink together. Someone picks out old L.A. hardcore songs on the jukebox to correct for the sins of the person who picked out a block of Texas swing. Someone else picks out masterpieces of East Coast hip-hop to correct for the sins of the person who picked out the block of hardcore songs. They generate friction, these off-duty waitresses and delivery guys and dog walkers. They rub elbows and bellies and backs, and together they hold winter and its wolves at bay.

Billy finds Anil Mallick at the end of the bar, where he is managing to defend two stools against the throng through some combination of fast talk and physical maneuverings. Anil is a chubby guy who wears half-moon spectacles and favors tweedy blazers; his round head is topped with a sumptuous mass of lanky curls; he works in the kitchen at a sandwich shop, but anyone here, in this bar, could mistake him for a kinda hot young academic. Anil is Billy’s coworker and oldest friend, and Anil, tonight, is testy.

“I thought you were just going to get cash,” says Anil. “You’ve been gone for”—he checks his watch—“twenty-two minutes.”

“Yeah, sorry,” Billy says.

Anil regards this apology. “There’s a bank literally two doors down from here,” he says.

“Yeah, I just—got distracted.” Billy puts the banana on the gouged bar, between them. “Take a look at this.”

“A banana,” Anil says.

“Right, but, where did it come from?”

Anil blinks.

“I mean, yes,” Billy says. “It’s a banana. We get bananas from, what, from the bodega.”

“Sure,” Anil says, patiently. He sips his Scotch. “Like a lottery ticket. Or cigarettes.”

“Well, sure,” Billy says. “Except a banana isn’t like a lottery ticket or cigarettes. I mean—it has to grow.”

“Cigarettes grow,” Anil says.

“Yeah, but—hear me out.”

“I am hearing you out.”

“We live in Brooklyn,” Billy tries. “It’s the middle of November. And yet we can go into any corner store and buy a banana. Where do they come from? Who grew them? I mean, I go into the store to hit the ATM, and I see these bananas sitting there, and I just stand there for a second, in the store, looking at them, and I’m thinking about, like, Costa Rica or Ecuador or some shit and it’s just—I’m sorry, but it’s just blowing my mind a little.”

“This took twenty minutes?” Anil says.

“I thought that you, of all people, would appreciate the fundamental weirdness of the whole thing.”

“You left me here for twenty-two minutes,” Anil says. “Are you asking me to believe that you spent a significant portion of those twenty-two minutes staring at a banana in some kind of trance? Forcing the better-adjusted members of our fair city to steer around you to complete their own humble transactions?”

Billy frowns. “Admit that it’s weird,” he says.

“It’s not weird! It’s normal. Humanity has at least eighty thousand years of commerce under its collective belt; the details of that should no longer seem opaque to you. You want to talk weird? Open a newspaper. Last week? You see that thing about the Starbucks in Midtown that disappeared? They think the employees went on the run together, stole everything out of it to sell on the black market or something. That’s weird. The shit that happens to you is not weird.”

“Commerce is weird,” Billy says. “I mean, think about it. People buy things.”

“And I,” Anil says, “am buying you a drink. Put that goddamn banana away.”

Here’s the thing about Billy. Bananas are not the only things that get him going. It can be anything. Just a week ago he was on the subway, sitting across from a woman with a tiny dog in her purse, and as he watched her tickle the little goatish beard under its chin he made the mistake of beginning to think about the very existence of dogs in general. People have pets. He repeated it. People have pets. It began to become odd; the very concept of pet began to slide out of his grasp. How did it get to the point, he wondered, where we began to keep animals as, like, accessories? He spent the rest of the ride staring at the dog, thinking basically: Holy shit, human beings, the shit they come up with. When he got back to his apartment he looked up dog in Wikipedia and from there started opening tabs and lost the rest of the day. By midnight, he had drifted to looking at videos of fighting Madagascar cockroaches, actually developing opinions on the cockroach-fight-video genre. He was cold. He was alone. He was uncertain as to what exactly had happened.

It had long been like this.

Blame his father: Keith Ridgeway, a pipe-smoking antiquarian bookseller, who had filled the entire first floor of the family’s gabled three-story Victorian house with books. Billy had spent his formative years wandering among heaped codices, studies and catalogs and compendia, brochures and pamphlets, extended inquiries into every conceivable topic. From the very existence of these books he learned one primary truth: that everything in the world was enveloped in great skeins of mystery into which one could bravely probe but which one could never fully untangle.

Blame his mother: Brigid Ridgeway, a professor of medieval studies at the local university, who tied her red hair in a long braid and kept a collection of a dozen swords in a restored barn at the rear of the property. Billy remembers her standing in the sun-drenched open space of the barn, on Sunday morning

s, practicing thrusts and parries, grunting and sweating, her heavy feet thudding on hard wood. Afterward she would spend hours at a workbench making chain mail. For fun. When Billy thinks back on her, he remembers her looking him in the face and telling him that she loved him, that he was special. Special and unique. From this, he learned a lesson that she may not have intended: that his differences were his merits. She loved him, he believes, because he wasn’t normal, he wasn’t a boy who was rambunctious and active and courageous, but rather a boy who was dreamy and inquisitive and delicate.

But now he is thirty, and his mother is dead and his father has drawn back into some sort of isolating crankdom that Billy doesn’t quite understand. And when Billy checks in with his peers, when he looks at pictures of their kids on the computer, he notes that they’ve all begun to amass some share of money or power or career advantage or relationship stability. Then he looks at himself. He’s barely managed to amass a goatee. He’s unmarried. He’s skinny. His mess of strawberry-blond hair is not quite receding, but it is thinning enough that it generates some small anxiety when he checks on it in the mirror. He makes $12.50 an hour at a sandwich shop run by an angry Greek. He’s still writing, yes, but what does he have to show for an entire adult life pursuing his quote-unquote craft? Half a novel, plus some short stories (gathered into an unsellable collection that in a fit of self-abnegation he decided to entitle Juvenilia). These moments of accounting lead him to understand that somehow he is exactly the same as he’s ever been: curious, confused, poking out an existence from which can be derived no clear utility. And in these moments Billy wonders if maybe he wasn’t wrong about believing that his differences constituted his merits. On certain days he wonders if he, in fact, has any merits whatsoever.

“So,” Anil shouts, over the growing roar of the bar. “Denver.”

Billy winces, turns his empty shot glass around in a circle.

“You said you wanted to talk about her,” Anil says.

“I know,” Billy says. “It’s just—things with Denver and I are really, uh, challenging right now.”

“You might as well tell the story.”

“It’s hard to know where to start. I mean, I guess it started when Jørgen disappeared.”

“Wait. Jørgen disappeared?”

“Oh, man. I didn’t tell you this part?”

Anil removes his glasses with one hand so that he can press his other hand slowly into his face.

“I mean,” Billy says, “he hasn’t disappeared disappeared. Like, I don’t need to call Missing Persons or anything. He’s just—not around.”

“Jørgen’s a tough guy to lose,” Anil says.

True. Jørgen, Billy’s roommate, is six foot four, with shoulders that give you the impression that there are certain doors that he can only get through by turning sideways. A big, broad, hairy dude. Basically a Wookiee who has maybe shaved a bit around the facial area. But nonetheless, he is, indeed, somewhat lost.

He had sat down with Billy one morning, two weeks ago, over breakfast—eating half a box of Cap’n Crunch’s Peanut Butter Crunch out of his mixing bowl, while Billy picked at two pieces of toast—and he’d explained to Billy that he was going to be attending some kind of electronic music producers’ conference, so he’d be away for a little while.

“Cool,” Billy had said, breaking off the corner of a piece of toast, blasting crumbs into his pajamas and the recesses of the couch. In retrospect, Billy probably should have gotten more information, but he assumed he’d hear more details before Jørgen left. But Billy hasn’t seen him since that morning. Two weeks now. Maybe producers of electronic music have these epic conferences that Billy doesn’t know about? That go on for, like, a month? He tries to picture what a hotel might look like after two weeks of being inhabited by dudes like Jørgen and all he can picture is the scorched landscape of some heavy metal album cover, littered with chunks of rubble that look like fragments of a blasted monolith.

Two weeks with no sign of Jørgen: maybe Billy should have been more worried. But he’d been enjoying having the tiny apartment to himself for a while. It had given him an opportunity to finally attempt to have a private sex life with Denver.

Denver, a filmmaker, lives in Queens. She shares her co-op house with eleven other people. She sleeps in a hammock in the attic; somebody else sleeps in a hammock at the other end of the attic. Her place is not a viable site for sexual activity. Not that Billy’s place is any better. He sleeps in a loft above the apartment kitchen, and the loft doesn’t have a door. In fact, it only has three walls. Basically if you’re standing in the living room you can see directly into the loft. Especially if you’re six foot four, like Jørgen.

To make matters worse, Jørgen stays up late, sitting in the living room till one or two a.m., smoking weed and listening to drone metal albums on his (admittedly awesome) Bang & Olufsen unit. Thank God he uses (admittedly awesome) wireless headphones; this at least gives Billy and Denver a chance. But adults shouldn’t have to fuck like that, trying desperately to finish before some third party decides to turn around. And the whole experience of rushing it? The clenched teeth, the film of flop sweat emerging on his forehead, the near-total uncertainty as to whether Denver is deriving any joy or pleasure or comic relief from the experience? It all cancels out whatever pleasure he gets from the grudging orgasm his body eventually spits out.

He’d return to having sex in the backseats of cars except neither he nor Denver owns a car. He has considered, on more than one occasion, signing up for a Zipcar account just to have a place to furtively fuck, but he never gets far enough in this plan to actually propose it out loud. Something about imagining that hundreds of other people around the city had also come up with this idea, and that he might end up fucking Denver in some car that somebody else had just used as their own roving fuckatorium … he envisions clenching buttocks, or a woman’s greasy footprint stamped on the window, and queasily dumps the whole idea.

So he was excited when he knew that Jørgen would be away. He’d used money that he didn’t really have to buy a nice bottle of wine, the start of a plan for a good evening. He’d told Denver that they’d be able to have some time alone. She’d been excited and pleased. Which was good. They were approaching the six-month mark in their relationship. A tricky point in a relationship, that six-month mark. Half a year in. Assessments get made when you’re half a year in. Half a year in is a good moment to instill excitement and pleasure, Billy thought. He thought it would maybe be the right time to say I love you, a task he had not yet accomplished.

Except then somehow he’d blown it. He’d gotten nervous about the exact scheduling of what he had come to think of as “The Event.” He’d been surprised that Jørgen had left as soon as he had after the conversation, and then had gotten confused about not knowing when exactly Jørgen was destined to return. So he began to hedge on inviting Denver over. Part of him thought that he should just call her over as soon as possible—immediately—but for the first couple of days he wasn’t entirely sure that Jørgen had, in fact, actually left. And then after that it seemed probable that he could return at any moment.

Billy sent a series of texts. He sent two e-mails of inquiry to the address that he thought was current for Jørgen. He even sent an e-mail to the address that he was pretty sure Jørgen wasn’t using anymore (Hotmail? That can’t be right, he thought, even as he was sending it). None of these efforts yielded any response. And a couple of days ago, with Jørgen already gone for twice as long as had ever seemed probable, he had to face up to the fact that he’d blown it. There would be no Nice Evening, no Event.

When he explained this over the phone, Denver had pointed out that if the Nice Evening had been truly important to him he would have been more careful to get a more detailed explanation of Jørgen’s plans.

“It is important to me,” he’d said. “I mean, it was important to me, I guess. I’m just—I’ve just never been good with details. That’s just part of the way I am.”

; “So,” she’d said, after a pause. “What you’re saying is that you’re a fuck-up.”

“Not—not a chronic fuck-up.”

She’d pointed out that she could come over right now and they could still have a Nice Evening. The odds that Jørgen would choose this specific night to return—didn’t it seem unlikely? And it did seem unlikely. But Billy had gotten it into his head that the Evening was now impossible, and somehow he was unable to disabuse himself of this notion.

“Why don’t you just call him?” Denver had said. “Instead of sending e-mails and texts?”

Billy had responded with a kind of tsking sound. “That wouldn’t do any good. Jørgen’s one of those guys who never actually uses his phone to, like, receive a phone call. If you can’t reach him by text you might as well just hang it up.”

“You could try,” Denver said, an uncharacteristic pleading note entering her voice.

“I don’t know how to put this without it sounding bad?” Billy said. “But that idea has just basically no value.”

The conversation began to go downhill from there.

“Look,” Anil says, after Billy has explained enough of this. “Just cut to the chase.”

“The chase,” Billy says. He knocks back the new shot that the bartender has set up for him. He wipes his chin with the back of his hand. “The chase is that at the end of it she said she just wanted me to say one thing. She just wanted me to tell her that everything was going to be okay and that things were going to get easier from here on out.”

“Okay, yeah,” says Anil. “And you responded by saying—?”

“I responded by saying that it would be ethically unsound for me to make a claim, for the purposes of comfort, that I couldn’t be certain was true under the present circumstances.”

Anil opens his mouth and then shuts it again. Finally he offers this: “No offense, man, but you’re a fucking idiot.”

“I’m aware.”

“Fucking,” Anil says, ticking it off on his thumb. “Idiot,” he concludes, ticking this one off on his pointer finger.

The Weirdness

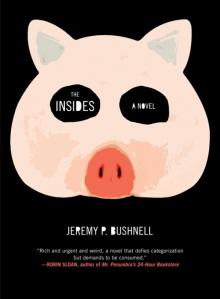

The Weirdness The Insides

The Insides