- Home

- Jeremy P. Bushnell

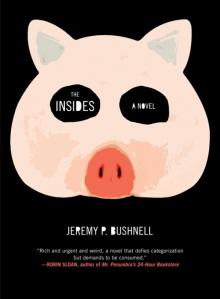

The Insides

The Insides Read online

Praise for The Weirdness

“Wonderfully weird and entertaining.”

—Esquire

“An utterly charming, silly, and heartily entertaining coming-of-age story about a man-boy who learns to believe in himself by reckoning with evil … a welcome antidote to heavy-handed millennial fiction. Instead of trying to find profundity in party conversation or making his readers shudder in melancholy recognition of their thwarted lives, The Weirdness finds virtue in absurdity. Thank goodness—or darkness—for that.”

—The Boston Globe

“Arriving as a practitioner of such supernatural humor, loaded with brio, wit, and sophisticated jollity, like the literary godchild of Max Barry, Christopher Moore, and Will Self, comes Jeremy Bushnell … An engaging reading experience.”

—Paul Di Filippo, Barnes & Noble Review

“In many ways, this is an illuminating parable for these times … you’ll just wish you had more of this delightful novel still left to read.”

—San Francisco Bay Guardian

“A whimsical approach … an aspiring author in New York who wakes one day to find that Satan has just brewed him a cup of fair-trade coffee—and has a little deal to discuss.”

—Tampa Bay Times

“[The Weirdness] is immensely entertaining, and more than being merely diverting, is truly funny.”

—Harvard Crimson

“The novel is truly a ‘weird’ read, though unforgettable … An open-minded, modern reader will fully appreciate this bizarre and unusual work of fiction, the author’s first novel.”

—Fairfield Mirror

“Absolutely, positively one of the most original takes on the nearing middle age, suffering male writer bit … Bushnell manages to turn this story on its head in what should be the most ridiculous novel you’ve ever read.”

—The Picky Girl

“A comedic literary thriller situated between the world of Harry Potter and the Brooklyn of Jonathan Ames, Bushnell’s debut effectively mines well-trodden terrain to unearth some dark gems.”

—Publishers Weekly

“The Weirdness manages to soar beyond the potentially familiar tropes of urban fantasy with a strong sense of style and character … Bushnell’s debut novel is a clever, darkly satiric tale of the devil, literary Brooklyn and the human penchant for underachievement.”

—Shelf Awareness

“This book is wild. And smart. And hilarious. And weird … in all kinds of good ways. Prepare to be weirded out. And to enjoy it.”

—Charles Yu, author of How to Live Safely in a Science Fictional Universe

“Jeremy Bushnell has written an irreverent, chaotic, comically inventive novel that makes New York City look like the insane asylum some suspect it is. It steadfastly refuses to bore you, and by the end has something important to say about the way we dream.”

—William Giraldi, author of Busy Monsters

ALSO BY JEREMY P. BUSHNELL

The Weirdness

THE INSIDES

Copyright © 2016 by Jeremy P. Bushnell

First Melville House Printing: June 2016

Melville House Publishing

46 John Street

Brooklyn, NY 11201

and

8 Blackstock Mews

Islington

London N4 2BT

mhpbooks.com facebook.com/mhpbooks @melvillehouse

Ebook ISBN: 9781612195476

Design by Marina Drukman

v3.1

TO MY FAMILIES

Contents

Cover

Other Books by This Author

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Prologue

Fifteen Years Later

1: Carnage

2: Demonstration

3: Heartbreakers

4: Indulgences

5: Fields

6: Pathfinding

7: Distraction

8: Triangle

9: Thing

10: Attempt

11: OVID

12: Advances

13: Cleaving

14: Killing

15: Hello

16: Professionals

17: Monarchs

18: Moving

19: Living

20: Minty

21: Listening

22: Tricky

23: Gaps

24: Here

25: Safe

26: Escapes

27: Inside

28: Homes

About the Author

There is a time in life when you expect the world to be always full of new things. And then comes a day when you realize that is not how it will be at all. You see that life will become a thing made of holes.

—HELEN MACDONALD, H Is for Hawk

You want to know what it’s like in there? The fact is, you spend all those years trying to make something of it. Then guess what, it starts making something of you.

—Μ. JOHN HARRISON, Nova Swing

PROLOGUE

When Ollie was eighteen she was given a decision to make. And she never would have made the decision to follow the warlock if it hadn’t been for his dog, which was about the friendliest-looking dog she’d ever seen. She’d been sitting on the wide concrete rim of a fountain in Tompkins Square Park and the mutt came trotting up to her, his enormous brown ears alert. He put his massive paws up onto her knees, locked eyes with her, and plopped his muzzle into her waiting hand.

“Oh, hello,” she said. She turned the dog’s head this way and that, admiring the messy mix of gold and brown and cream in his face. He had a red bandanna tied around his neck, so she guessed he had an owner nearby. She looked up, in search of the owner, and then she found him. The warlock.

She never would have made the decision to follow him if he hadn’t been young, like her. He might have been a little older: she guessed nineteen. When you’re an eighteen-year-old girl spending most of your days wandering around the city, you come across a fair number of people, mostly men, who try to get you to follow them somewhere. Lots of them are older, sometimes way older, and Ollie had learned that the guys who are older almost always meant bad news in one way or another. Not that younger guys were ever totally safe: they weren’t; she’d learned that, too. And so Ollie gave this guy the quick assessing look that by this point in her life she’d pretty much mastered. In quick succession she noted his grubby black T-shirt, his gray utility pants, his tattooed hands, his scruffy beard, his unkempt hair. None of it gave Ollie much confidence that he might be trustworthy, that he might be anything other than a threat in a city full of them (except maybe his hair, which mirrored her own in its kinky wildness). But having the friendliest dog ever half up in her lap had lowered her defenses just enough for her to give the warlock a second look, and this time she looked at his eyes, at his lips, and she noticed an openness there, a kindness. It’s not that he wasn’t looking at her with attention, with interest—he was—but he was also looking at her without cruelty. With intention, yes, but without calculation. She wasn’t used to experiencing one without the other. She almost didn’t know what to do with that. It knocked something loose in her sense of what was possible, in a way that was, frankly, a little bit scary.

So she wouldn’t have followed him if she hadn’t also been with her friend, Victor, a queer Colombian kid she knew from the group home, her companion all through that summer. He wasn’t her protector or anything—he was only about half her size, so she was pretty sure that in the event of a real throwdown she’d be the one protecting him—but that wasn’t the point. The point was that there was safety in numbers, always, that people were way less likely to fuck with you when you were with somebody else,

anybody else.

So when the warlock—his name, they’d later learn, was Gerry—asked them what they were up to, Ollie said, “Nothing” instead of “Leave us the fuck alone.” And when the warlock asked them if they wanted to see something cool, Ollie said, “Sure.”

And then the warlock took them to the second floor of an abandoned building and showed them something cool.

It was something like an altar, or a workbench, or a shrine. It was a long flat table surrounded by a collection of symbols graffitied onto the walls behind it and by a set of eclectic artifacts arranged on the floor. A bleached cow skull, a cracked Virgin Mary figurine, an outlet strip, a belt buckle with a picture of a sixteen-wheeler on it. The friendliest dog sniffed around, pushed a few items out of place with his nose; Gerry didn’t seem to mind.

“What is all this?” Ollie asked.

“Magic,” Gerry said.

Ollie and Victor didn’t say anything. Ollie didn’t know if she believed in magic or not but she knew that the room was very beautiful and that it held within it a kind of meaning that she didn’t often get the chance to experience. She knew that she wanted to spend more time inside rooms like this, if she could.

“What would you say,” Gerry said, “if I told you that, using nothing more than the items in this room, you could get anything you wanted?”

“I’d say you were a fucking liar,” said Victor.

Gerry smiled. “Fair.”

“You don’t look like someone who has everything he wants,” Victor said.

“Don’t I?” Gerry asked. He was sitting on the floor, cross-legged, scratching his dog behind the ears. Victor didn’t answer.

“Let me ask you,” Gerry said, “just to think about this question. If you didn’t think I was a fucking liar—if you really did think that, after a period of apprenticeship, you could get whatever you wanted—what would you want? Don’t tell me the answer. But think about it.”

Ollie didn’t know whether Victor was thinking about the question, or what his answer might have been. But her own answer came to mind immediately. A family, she thought. I would want to be in a family.

“You come up with something?” Gerry said, after an interval of time had passed. Ollie nodded, just the tiniest nod. She looked over at Victor and saw him offering his own tiny nod as well.

“OK,” said Gerry. “In a minute, I’m going to ask you to decide if you want to join us, to embark upon doing a kind of work with us. If you do the work, you’ll get what you want. You don’t have to. I’m not twisting your arm. You can just walk out of here and go back to whatever you were doing before I came along. That’s totally OK. But before I ask you to make the decision, I need you to think about one other thing. I need you to think about the Possible Consequences.”

He paused for import, which made Ollie want to roll her eyes, but then the pause went on, and stopped seeming silly. She listened.

“It’s really important that you think about those, pretty seriously, before we get started,” Gerry said. “Because that’s the thing about magic. At first it seems awesome to be able to get what you want all the time, but getting what you want always has consequences, and you’d better know what those are, because they’re going to bite you square in the ass, every time. If that’s going to make you reconsider wanting what you wanted in the first place, it’s better to know before you get started bending the whole Goddamn universe this way and that.”

Ollie thought about it. But she was only eighteen. She wasn’t very good at thinking about the far-off consequences of things that probably wouldn’t happen anyway. I just want a family, she thought. What’s the worst that could happen?

Fifteen Years Later

1

CARNAGE

The meat begins to arrive. It arrives in refrigerator trucks stenciled with the silhouettes of majestic steer. It arrives in plain white delivery vans driven by mellow Iranians, quiet masters of exsanguination. It arrives in the trunk of Ulysses’s Buick, which has been lined with rubber blankets and packed with ice. He digs out four heirloom chickens beheaded this morning, upstate, and hands them off to Ollie, same as he’s done every Friday this summer. They will later be artfully turned into eight plates and served in the private dining room, at around a 200 percent markup over what Ulysses gets paid for them, which is already a sum that does not fail to impress Ollie anew every time she signs off on an invoice.

Her name is Olive Krueger; she goes by Ollie; her signature, made in haste, is an elongated, runny O.

Even though Ulysses’s beard has gotten a little gray and wild, and even though his teeth are as crooked as they’ve ever been, he is still, Ollie thinks, one awfully handsome man. His short-sleeved work shirt, patterned in a pink strain of lumberjack plaid, is worn tight across his chest: the sight invites her to remember what his body looks like, even though the memories are part of a thicket which is not without thorns. She turns away, hands the chickens off to Guychardson, her co-worker, a wiry Haitian with a rockabilly hairdo, who has emerged from the kitchen to help with the unloading. When she turns back, Ulysses catches her eye, gives her the look that asks if he’s invited to stay for a minute. She gives him the look that says OK.

It’s a qualified OK. Not: OK, come on in, hang out as long as you want, like everything’s normal, like we’re back to fucking again; more like OK, you can stand with me, here in the loading zone, for exactly as long as it takes me to smoke one cigarette. Don’t talk too much.

And he doesn’t. They don’t have that much to say, these days. She doesn’t want to talk about the past, and the future, in the absence of either of them making some major change, just looks the same as this. So all they’re left with to remark upon is the present.

Ulysses leans on the railing, squints up at the segment of hazy sky visible between the buildings. “Supposed to be in the nineties again today,” he says.

“Fucking August,” Ollie says.

She looks over her shoulder: Guychardson’s still inside. She takes Ulysses’s collar in her fist. Because they’re unobserved, she feels at liberty to pull him away from the railing, pull him in close, kiss him ferociously on the mouth.

This is a thing she does with him only sometimes, often enough to be familiar but not so often that either of them can allow it to settle into an expectation.

She uses her tongue. He tastes like violet: it’s that gum he’s always liked. She probably tastes like a Marlboro Red. She never really enjoyed this style of vigorous kissing but she knows that Ulysses likes it, and she likes thinking that giving him a taste of her will give him something to remember as he heads back upstate. She likes thinking about him wanting her from 150 miles away. She might not even want him any more, but she still wants him wanting her. She’s not entirely sure what that means but she doesn’t feel like figuring it out right now, not at this point in her life.

And then she feels eyes on her. She breaks the kiss, looks over to see a Greek guy wearing a nylon Red Bull jacket coming up the stairs at the end of the loading dock. Greek dude is scowling, which makes her vigilance kick on: thanks to her fucked-up youth she still can’t see someone scowling at her without trying to reason out exactly why, trying to figure out what exactly is coming at her. She suspects that what’s coming at her, in this instance, is some racial shit, especially if he thinks she’s a white woman, which he almost certainly does. White guys, like Greek dude here, don’t always like it when they see white women making out with black guys, like Ulysses here. So it could be that. Or it could just be his face’s default demeanor. She repeats a thing that Donald used to tell her: not everybody is your enemy. You live in a city, he would say, sometimes people are grumpy for reasons that have nothing to do with you.

Regardless: this man’s appearance means that more meat has arrived. She slaps Ulysses on the shoulders and grins at him by way of goodbye, and once he’s strolled back to his Buick she takes Greek guy’s clipboard and signs for six skinned and hollowed goats. Guychardson returns, and the t

wo of them load goats up on their backs and head into the kitchen, out of the heat of the day.

Part of their job is to make all this meat go somewhere. She passes the three walk-in refrigerators without a look; space is at a premium in there and the carcasses are too large to fit. The rule at Carnage is that nothing goes in the walk-ins until it’s been sundered. So instead she loads the carcass into the dumbwaiter. Guychardson is right behind her: he loads his goat next to hers in the dumbwaiter’s double-wide car, and punches the button that kicks on the motor. Ollie heads downstairs.

The building used to be part of the waterworks system, or something; Ollie’s not up on her New York City infrastructure enough to be able to say for sure. All she knows is that the Carnage basement is a huge length of semicircular tunnel, lined in clammy antique tile. Once the tunnel went somewhere, she presumes, but now it terminates at both ends in crudely masoned brick walls. Beneath her feet, ovoid grates mark out eight-foot intervals on the floor; through them she can hear the distant sound of water, running through some vast dank sequence of caverns beneath Manhattan. Above her are the hooks.

The room—windowless, subterranean—stays cool all year, even now, in the long, sweltering stretches of summer. Part of the reason Jon and Angel even set up in this building in the first place, as the lore goes, was because they saw this room as a quick-and-dirty solution to the problem of where to put all the meat they were going to need in order to make this venture work. Install some hooks on a track in a vast cool space and you got a start.

She lifts the goat. She can do this a hundred times a day: she’s six feet tall and has her father’s Germanic-peasant arms. She also has her mother’s welter of wild curls. In a perfect world these would be minor entries in a long list of gifts she’d received from her parents: in this world, though, they’re the two best things she got.

She returns to the dumbwaiter, where there are two more goats for her. This repeats until all six goats are on hooks, and then she heads back upstairs to start working on the pigs.

The Weirdness

The Weirdness The Insides

The Insides