- Home

- Jeremy P. Bushnell

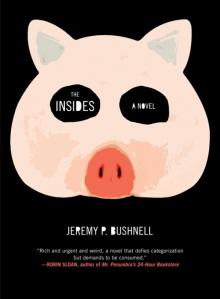

The Insides Page 5

The Insides Read online

Page 5

She claps the lid of the box shut, places it back into the drawer of the end table.

It’s amazing, she observes, with her hand on the drawer’s porcelain knob, just how much you can stuff down inside you. Just how much will fit, if you force it.

“Sorry.” A voice—male voice—at the doorway to her bedroom. She’s only wearing a long men’s undershirt, and violence flashes through her mind, a sudden scene of it, something that could be about to happen to her. But the voice is light and timid and the old fear doesn’t last: she knows who this is. It’s Victor’s hookup from last night, just the latest in a string of guys who come through the apartment and occasionally find their way into her bedroom by accident. Largely by accident. Every once in a great while with some sexual intention. And that doesn’t always work out badly, but she gets one look at this guy and she can tell you that this isn’t that, even though all this guy is wearing are a tight pair of black boxer briefs of the sort that Victor calls boy panties. He’s every inch Victor’s type: compact, muscular, curly black hair, olive-skinned. Ethnicity tough to peg. For some reason Victor makes a big show out of his refusal to sleep with other Colombian guys, and it’d be a bad guess for this guy anyway, whose features skew a little more Hebraic. Both of his nipples are pierced with tiny steel barbells, giving his chest a look that Ollie thinks of as perky.

“Looking for the bathroom?” Ollie says.

“Yes, please?” says the hookup.

“You want the second door on the left,” Ollie says. “This is the first door on the left.”

Hookup leans out the door again, looks down the hall, leans back in, a smile across his face. Perfect teeth, she notices, again in keeping with Victor’s taste. “Thanks!”

“You got it,” says Ollie, and she gives a little thumbs-up and then falls back down to the pillow, pressing her face into it, inhaling the metallic stink. A second later she can hear the pipes in the wall shudder into life, the slosh of water falling into the clawfoot’s wide basin.

“Isn’t he a dear.” Another voice at the doorway: Victor. She pulls her head up a second time. His body type is nearly identical to the hookup’s and he’s wearing the same style of underwear, only patterned with maroon and cream stripes. No nipple studs: Victor’s decorative gesture is a crucifix on a slender gold chain.

“He’s fine,” Ollie croaks. “You think you’ll be keeping this one?”

“Oh, no,” Victor says. “A young thing like that, his whole life ahead of him? It would be cruel.”

“I thought you delighted in cruelty. Didn’t you say that once? Something something its exquisite grandeur?”

Victor makes a tch sound with his tongue, as though she’s misjudged him terribly, and then he comes and gets into bed with her. They go way back, Victor and her, and this is not an uncommon way for them to begin the morning. It’s affectionate but not sexual, even though this morning she can smell the musk of fucking on him, and his semihard penis pokes her naked ass as he snuggles up behind her. She grumbles and pushes him back an inch, her palm into his face.

“My sweet,” Victor says, and when she goes just a beat too long before responding he props himself on an elbow and asks, brightly, “What are you thinking about?”

What is she thinking about. The same stupid stuff. The farm. The broken circle which used to be Ollie and Donald and Jesse. She could admit this to Victor. He’s the one person from her adolescence who she’s held on to in adulthood, and so he already knows the whole sad tale. He knows the pre-farm Ollie as well as the post-farm Ollie, just like she knows the pre–Food Network Victor and the post–Food Network Victor. And she’s confided in him before on mornings like this one, mornings when she misses the life she made for herself. Sometimes it feels good to miss it out loud, while Victor strokes her hair sympathetically. But sometimes she’s not in the mood. Sometimes it feels pathetic to still regret a mistake you made a long time ago. Sometimes you have to front like you’re strong. Isn’t that the way, she wonders, to actually become strong? Fake it till you make it, like the alcoholics say?

But Victor still awaits her answer. What else is she thinking about, she wonders, trying to remember. She thumbs the scar tissue on her finger, a piece of nervous habit usually, but today it reminds her of knives, which reminds her of Guychardson, which gives her something to offer to Victor, something to get him off the trail of the real answer.

“I’m thinking,” she says, “about a knife.”

“A knife?”

“A magic knife.”

Victor may have ended up turning into a pastry chef instead of a warlock, but he still uses the magic he learned from the street magicians, usually to get himself nudged back into the limelight, with only partial success. He’s always nagging her to get back to practicing, too, so she knows this answer will satisfy and intrigue him.

Which it does. His eyes light up immediately.

“It may not be magic,” Ollie confesses. “I don’t know. But I kinda think maybe.”

“Show me,” he says.

“Not my knife,” Ollie says. “It belongs to some guy at work.” And she tells him about Guychardson, about the racing.

“You say you’ve worked with him for a year?” Victor asks, when she’s through.

“A year, yeah.”

“You’ve been in the room with this knife for a year and you only mention it to me now?”

“It’s only twice a week,” Ollie protests. “Fridays and Saturdays.”

“That’s one hundred times you and this knife have been together. One hundred opportunities to hold it.”

“To caress it,” she says, mimicking him.

“To learn something about it!” he says. “You missed all one hundred?”

“Not everyone has the same hard-on for magic stuff that you have, you know.”

“Ut!” Victor says, holding up a hand to halt her. She makes a face, slaps her fist into his palm.

The hookup appears in the hall again, a towel wrapped around his waist. Ollie notices, somewhat grimly, that it’s her towel.

Victor eyes the hookup, kisses the air near her ear noisily, and springs out of her bed.

“This conversation,” he says from the doorway, pointing at her with two fingers, as though they were the barrel of a gun. “It isn’t over.”

“Go away,” she says. “Both of you.”

4

INDULGENCES

Maja sips water from a paper cup and watches Unger use his hammy fingers to punch a number into an obsolete-looking phone.

“Hello,” he booms into the chunky black thing. He holds it away from his head and eyes it balefully, as though it is in the process of bewitching him. “Hello. Hello, Martin?”

The tinny squawk of a voice on the other end of the line.

“Martin,” Unger says. “Maja Freinander is here. Yes, the Finder. She’s expecting to begin soon. Are you meeting us?”

Maja eyes the disintegrating file folders on the desk, lets some of their histories drift into her. Visions of libraries begin to unfold.

“No, Martin, no, we’re at the office,” Unger says. “We were—you were supposed to be meeting us here, at the office.”

A pause. Maja suspects that this piece of information is in no way news to Martin. She lets another library accumulate in her mind.

“Yes, Martin, I understand, it’s just”—Unger sighs here—“no matter, nothing to be done. Where are you now?”

Unger pins the phone between his ear and his shoulder and rummages in a desk drawer with both hands until he emerges with a chewed-up ballpoint pen and a memo pad.

“And,” he says, “is there a place around there that we could meet?”

Unger takes his car, and Maja takes hers. She’s partially following Unger and partially following her emerging sense of the way. The drive takes half an hour and it leads them through pretty tree-lined roads which occasionally give way to road crossings marked by the presence of commerce. Generic stuff, mostly—drug stores, gas

stations—but there are also appearances of a more occasional type of shop that Maja interprets as local oddities. A place called the Doll Barn, for instance. It’s actually in a barn.

They end up at a place called Zingers Dairy, an eatery with exterior signage that’s done up in a loud scheme of black-and-yellow zigzags.

She follows Unger in. Everyone inside is eating ice cream. Gabbling teens and fattening families. And, among them, one adult-aged male sitting alone. His head is shaved, his chin is dark with two days’ worth of growth, his olive T-shirt is grubby, his eyes are hidden by cheap-looking sunglasses. He is bent over a huge banana split sundae, which he’s working his way through with clear method and intention, as though eating it is a joyless task but one that he intends to complete efficiently.

“Martin,” Unger exclaims. Martin removes his sunglasses and looks up at his father. He lifts his napkin and blots it firmly against his lips. He then turns to look at her, something indolent in the slowness of the motion. He’s older than she expected—she can see some gray in the furze of beard growth—but the smile he cracks here has its share of adolescent insouciance in it. It’s the smile of someone calculating exactly how much they can get away with. She meets it with a fractional nod, the most minimal of all her available hellos, the one designed to shut down as many possibilities as possible. His smile goes away but she has the sense that he’s maybe just saving it for later.

“You must be the Finder,” he says, extending his hand. She’s wearing her gloves, but to be on the safe side she opts to ignore it anyway, deliberately letting her attention flick to something else in the room. It’s a method that she’s adopted over the years: if you feign distraction at just the right moment, people usually allow the handshake moment to pass without necessarily concluding anything about you. When she looks back, though, Martin still has his hand out: persistent in a way that implies a certain doggedness. She puts it in a column of things that she’ll need to watch out for.

His hand hovers there, in front of her.

She opens her mouth to explain, but Unger cuts her off. “Martin,” he says. “She doesn’t.”

Martin looks at Unger, and then looks back at Maja, lowering his hand. For just a second he has the look that indicates that he’s considering whether she’s the most stupid person he’s ever met. It makes next to no impression on her: this is the exact look that you tend to get when people figure out that you’re a person who doesn’t shake hands. He blinks it away, resets his face into something benign.

“It’s Maja, right?” he says.

“That’s right,” she says.

“Well, have a seat, Maja,” he says. “You can call me Pig.”

“Martin,” says Unger, lowering his bulk into a chair. “You know how I feel about that revolting name.”

Regardless of how Unger feels about it, Maja decides that the nickname suits him. He’s not overweight—he has a wiry frame, built out with some muscle—but in his face she can see a mix of appetites, a propensity toward indulgence. It’s not only that, though: it’s also the particular sort of intelligence in his eyes, cold, a little brutish, something unfinished and raw and wet about it. Piggish, yes, that exactly.

Martin shrugs at his father and cuts through a banana with the edge of his spoon.

Maja sits, and in the brief silence that follows the Archive pipes up.

Well, it says, these people seem totally terrible.

She waits, and it asks the same question that it has asked her many times before: Are you sure you want to work with these people? We don’t need the money.

It’s important to have money, she thinks back at it.

We have money, it says. We have quite a lot of money. We could just go home.

We go home, she replies, when the job is done.

Then why do we take half upfront? the Archive asks. We take half up front so we can walk away whenever we want to.

And how many times have we done that? she replies. How many times have we left a job before it was over?

We’ve never done that, the Archive says. But we could.

We could, she admits. If it was impossible to do our job. If we were in danger.

If we were scared, says the Archive.

I’m not scared, she thinks. Not of these people. Are you scared?

No, admits the Archive, after a moment.

That’s right, Maja thinks. These people aren’t smarter than us. All we have to do is put up with them until the thing is done and then we take our money and we go and we never think about them again.

Pig looks up from his sundae, looks her in the face, his expression suddenly all concern. “Do you want some ice cream?” he asks.

Caught momentarily off guard, Maja shrugs, realizing only a moment too late that to show indecision was a mistake.

“Get yourself some. Go ahead, get some. A banana split on a hot summer’s day? Not much better than that.”

The air conditioning, of course, is blasting, so the hot summer day is not really perceptible, not as such. Actually, though, I wouldn’t mind some ice cream, says the Archive. For the moment, though, Maja holds her silence.

“Martin,” Unger says, after a pause, “let’s not waste any more time.”

Pig shows both his palms in a gesture of exasperation. “Jesus, Dad, let her get some ice cream,” he says. “It’ll take two minutes.”

Unger draws back into a stony silence. Maja starts working on a way to defer but Pig’s already in his pocket; he pulls out a wadded ten-dollar bill.

“Go get yourself some,” he says. “On me.”

Fine. Maja takes the bill, smiles thinly, and heads up to the counter. On a whiteboard are written the names of twenty-four different flavors. She eyes them with something like wariness. Texas Pecan. Candy Bar Whirl. Jamocha Chip. Moose Tracks. Extreme Moose Tracks.

“What can I get for you?” asks the clerk, a girl with braces, wearing a transparent visor.

“Extreme Moose Tracks,” Maja says, just to hear what the words sound like coming out of her mouth.

“Cup or cone?”

“Small cone, please.”

The girl processes the answer. “We have Child, Regular, or Double.”

This data annoys her. “Double,” she says.

Smart, says the Archive.

And in a minute she has her double cone, a terrifying amount of ice cream, and she goes and rejoins the party at the table. Pig regards her with a vague sort of respect as she tilts her head to lick around the edge of the cone: she half expects his giddy grin to return but it stays wherever he’s stored it.

In the ice cream she can taste an extensive network of refrigerated storage and, as a back-note, the near-flatline of cow consciousness. But despite that it remains, in its way, enjoyable. She uses her tongue to shape the tip of it into a point.

“May we begin now?” Unger says.

“Sure,” Pig says. “I want to begin with a question.”

Unger looks at Maja. Maja pauses in her ice-cream sculpting and says, “Ask.”

“My dad thinks it’s in Boston,” Pig says. “Is he right?”

“It’s not in Boston,” she says.

Pig taps the end of his spoon against the hard tabletop, once. Its clack coincides with a lull in the noise of the room.

“Three years we’ve been here,” he says, quietly, sullenly. He looks at her. He does not look at his father.

“Martin,” Unger says.

Pig ignores him, keeps his eyes on her. Absently, he takes both ends of the spoon in his hands and begins to apply pressure.

“You can tell us where it is,” he says. “That’s what you do.”

“That’s correct,” she says.

“Where is it?”

“New York,” she says. “New York City.”

“OK,” he says. “So we go there.”

The spoon’s metal bends at its weakest point.

5

FIELDS

Ollie breaks down a beef hindquarter, r

educes it to its primal sections. Five major cuts. Remove the flank. Remove the sirloin tip. Remove the loin. Seam out the shank. Separate the round and the rump. This is a sequence she performs daily; several times daily. Sometimes she performs it in her dreams. The steps are ingrained, literally memorized in her body, like a sort of dance. Which means that her attention is free to wander, even though one thing kitchen life has taught her is that you should never really let your attention wander too much, not when you’re working with knives.

And yet: her mind is not where it should be, not attending to the task, to the blade in her hand. Instead, she’s watching the blade in Guychardson’s hand, watching it move. He cuts along a femur, cuts perpendicular to the bottom knuckle. A basic cut, but there’s something off about the way he does it. It looks fake, like a movie. A movie where, for some reason, they needed to fake the act of butchery, render it in photo-realistic but unconvincing CGI. All the textures are right, but all the physics are wrong. Why would they do it that way, she thinks, losing herself in the idea. When they could just have gotten a real butcher.

She knows it’s not a movie. Guychardson is real. He’s right there, standing across from her. She can smell his sweat. She can hear him humming idly even over the choppy black sea of noise she has pouring out of the SoundDock. He’s too annoying to not be real.

Still, though, she watches him until she sinks into a light sort of trance. Her hands stop working. She sets her own knife down on the table.

“Guychardson,” she says. Or tries to say. Her voice catches, her throat unexpectedly dry. She coughs.

“Guychardson,” she says again. He pauses in his work, looks up.

“Let me see your knife,” she says.

Guychardson blinks, and then gives a sly smile and pulls the knife out of the knuckle he’s cutting through. He holds it out toward her, twists it in the air. The fluorescents glint off its weird double edges, creating some subtle optical effervescence, like something that would manifest at the onset of a drug trip.

The Weirdness

The Weirdness The Insides

The Insides