- Home

- Jeremy P. Bushnell

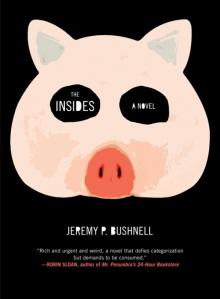

The Insides Page 9

The Insides Read online

Page 9

“Mildly,” Maja says.

“How much is mildly?”

“What are you really asking here?” she says, impatient with this line of questioning.

“Can you still find it?” Pig says, slowly.

“Yes,” she says. “We just have to do it a little differently. I’m going to stop trying to pinpoint where the blade is right now. Instead I’m going to figure out where it’s been. I’ll be—looking for the pattern of its movements instead of for the thing itself.”

“But you’ll still be able to find the thing itself.”

“Eventually,” she says. “But yes.”

“Yes,” Pig says, as if double-checking.

“Yes.”

“OK, then,” Pig says, and he grins a little bit; she allows herself to grin back in return. “So what do you need from me?”

She needs supplies. They stop at a Duane Reade and Pig purchases everything she points at: hand wipes, pens, highlighters, yogurt, a bag of almonds. A packet containing a pouch of tuna, some crackers, and a selection of spreads. A road atlas of Westchester County and Metropolitan New York.

All he buys for himself are three cellophane bags full of sour gummy worms.

She’s not sure how he continues to function; she hasn’t seen him eat anything but candy since they left Massachusetts, about nine hours ago now. She wonders if he’s going to hit a steak house in the middle of the night, wolf down a plate of red meat. But for now she sets the question aside.

What she needs next is a room with a desk, someplace where she could sit and concentrate. And so they drive into New Jersey, thinking it best to stay some distance from the thing they’re looking for. They stop at a Best Western motel and Pig saunters inside to the registration desk. She gets out of the car, walks to the furthest edge of the parking lot, stares into a tiny copse of ornamental pines. After the long day spent driving around in the city, it’s soothing to lay her eyes on something, anything, that hasn’t been built by human hands. She exhales, then twists at the waist, cracking her spine.

Pig rents two rooms, a suite separated by an adjoining door. Once she’s alone in her room she sits at the desk, turns on its tiny brass lamp. She peels off her gloves, uses the hand wipes. She eats the crackers and tuna and then turns her attention to the atlas. She spends a long time with it. She finds the pages that correspond to the places through which they drove, and she uses the pen to trace over certain streets. She marks specific points with heavy dashes, indicating certainty, certainty that the blade has crossed through those points. She works slowly, takes her time. She moves back and forth through the atlas for an hour, returning repeatedly to a few specific pages to ornament them more intensely, entangling them in dense thickets of ink. Eventually the process slows, as though she’s depleted some reserve inside her. She sits for a minute to be sure, and then turns back to the beginning of the section, so that she can examine all the boroughs at a larger scale. After a moment she draws a slash across it at a very particular angle. To this slash she adds two more. Together they form a triangle.

She knocks on Pig’s door, enters. He’s lying on the bed, over the covers, his boots still on, his head propped up with a pillow folded in half. He’s watching television with the volume turned all the way down to zero, eating worm after worm as televisual color plays across his face. He looks bland, harmless, almost goofy. But she knows it’s an error to think of him that way.

“Three points,” she says, handing him the atlas, indicating the triangle with the tip of her pen. “The knife primarily moves between these three points.”

He reaches out and traces the triangle with his finger. Two of the points are in Brooklyn, the third in Manhattan.

“What are these places?” he asks.

“I don’t know,” she says.

“So tomorrow we find out?” Pig says.

“Yes.”

She sleeps soundly, for the first time since arriving in America. She sleeps and she dreams, dreams of the Archive, and, as it often does, in dreams, it opens up to reveal the face of Eivind, her brother.

9

THING

“Oh my God,” Victor says. “Kill it.”

But neither of them make a move to do this. Instead they both take two steps backward.

The thing is a fat worm, about two feet long. Its body is composed of hundreds of transparent nubs, terminating in tiny little grasping suckers. Behind this seething tissue Ollie can see weird rudimentary organs clenching and pumping, a loop of slime being crudely circulated from one end of its body to the other. The worm contracts and contorts, smacks itself wetly against the baseboard.

“It’s going behind the stove,” Ollie says, trying to intuit some order in its chaotic twisting. “Don’t let it get back there!”

“OK, OK,” says Victor. He takes a step toward it, half-crouched, hands splayed open, like he’s an alligator wrangler.

“Jesus Christ, don’t touch it,” Ollie says.

Victor reels around to look at her, helpless, baffled in the face of these competing injunctions.

“We have tools for this,” she says, grabbing the handle of the nearest drawer. She jerks on it hard, too hard by half thanks to her fight-or-flight response: she’s left holding an empty drawer, swinging out behind her, while all the utensils spill across the floor in a cacophonous tide. The worm lashes back from the clanging mess, whips itself complicatedly into the legs of a bar stool.

“Tongs,” Ollie says, pointing at them with her foot.

“On it,” Victor says, scooping them up. He takes one step toward the stool and pauses there, considering his angle of approach.

“Don’t touch it,” Ollie says again, because she can’t think of what else might constitute good advice in this situation.

The worm uncoils, releasing the stool legs from its grasp, and throbs once, propelling itself toward Victor’s feet. Victor takes this opportunity: he darts in, gets the tongs around the worm’s midsection, and lifts it up to eye level. It writhes in the air. Ollie shrieks. Victor blanches.

“Now what?” he yells.

“The sink,” Ollie says, gesturing at it with both hands. Big motor movements seem to be about all her body wants to produce in this situation. “Get it in the sink.”

Victor lunges toward the sink and drops the worm in there, drops the tongs in as well, just for good measure. He steps way back and Ollie cautiously steps forward, taking his place.

“Kill it,” Victor says.

“Just wait a second,” Ollie says, leaning forward, trying to get a better look at the thing. It contracts and expands gently in its crude confinement, as though gathering strength, and then thrashes outward, whacking the side of the sink, which makes about the same sound as it would if you had just hit the steel soundly with a rubber mallet. Both of them jump.

Ollie reaches out and peels a cleaver off from the magnetic strip mounted on the wall.

“Kill it,” Victor says again, a little more pleadingly this time.

“Just a second,” Ollie says. “You ever think that our first response to this thing maybe shouldn’t just be kill it? We don’t even know—”

She has to pause here, because the list of what they don’t know is so lengthy that she can’t even select an option that would meaningfully fill in the blank.

The worm coils and then, as Ollie watches, it slowly extends one of its tips into the air, as if sniffing, although it doesn’t appear to have nostrils, as such. She can’t even say for certain that she’s looking at its head: it seems to have a total lack of sense organs. She has barely completed making this observation before it is rendered obsolete: a thin seam opens up along this risen end. The seam ripples and opens, revealing rows of needlelike teeth, and the worm hisses.

“Yeah, nope,” Ollie says, and she terminates this development right fucking now by bringing down the cleaver and lopping off the hissing part. The body twists reflexively a few times, black fluid spuming from the wound and splashing across the sink’s

stainless surface. And then it stops.

“OK,” Ollie says, still gripping the cleaver. She wants very badly to wash her hands but she’s afraid to put her fingers in the sink.

“We still have a problem,” Victor says, pointing at the portal, which still hangs in the center of the room. Maybe it’s just the extra adrenaline talking but it seems to have taken on a baleful aspect, like an accusing eye.

“You forgot,” Ollie says, pointing the cleaver at him accusingly.

“Forgot what?”

“You forgot the first fucking rule of this shit: don’t make something manifest if you don’t know how to banish it.”

“I knew how to banish it,” says Victor.

“You thought you knew, maybe,” Ollie yells. “But you were wrong.”

“Fine, you want me to say ‘I was wrong’? Will that gratify you?”

“A little bit!”

“OK, fine: I was wrong. But are you going to stand around enjoying being right or are you going to help me get this thing closed before it shits another snake into our kitchen?”

For the moment, she puts aside the fact that she’s supposed to be finished with doing magic, and instead she thinks: banishing ritual. She’s done banishing rituals hundreds of times; it’s one of the first things you learn when you’re learning magic. You gather your will, focus it, channel it towards the disruption of whatever craziness you summoned up. Normally it’s easy, like disturbing a reflection by dragging your fingers through still water. But this one doesn’t look like it’s going to be easy. So when it’s not easy, you reach for something that can help, something that can amplify your willpower. Wands, holy symbols, objects with deep personal significance, whatever—

“Tools,” she says. Victor shows no signs of hearing her: he’s staring abjectly into the portal. She claps her hands together to break his trance and regain his attention. “Victor! Tools! Magical implements. What do you have?”

“Bells? Sacred bells?” he says, after a moment.

“Awesome. Get them.”

“What do you have?” he asks her.

She considers the question for a second, tries to remember where any of her old magic shit might be. After a grudging moment—don’t do this, says the part of her brain that’s afraid to look at the past—she realizes that she might have something that will work. She bolts out of the kitchen, nearly colliding with Victor in the doorway.

She skids down the hall, finally coming to a stop in front of the closet. She yanks out the lumpy sack that contains Victor’s old air mattress and chucks it out of the way, letting it thud onto the floor. Behind it lies a beat-up cardboard box, the final repository of the occult claptrap that she collected in what seems like some former life. Objects with significance. She pulls it toward her and blows coils of dust off the top of the box with one sharp huff.

“OK, here,” she says, bringing the box to Victor. He’s working hurriedly to untangle a string of tiny bells that he retrieved from somewhere. Behind him, the rift undulates calmly. “There’s got to be something in here that will work,” she says.

“Open it up,” Victor says. She hesitates, then reluctantly plants the box on the thin strip of counter between the sink and the rangetop. She braces herself for just a second, and then she opens it, for the first time in years.

She sees a silver cup, a loop of prayer beads, a lump of wax. She sees an acrylic box that contains two human teeth: one of her own baby teeth and one tooth that fell out of her mother’s head in those final bad weeks.

She digs down a layer and comes upon a dirty zip-top bag that contains things that she kept because they connect her to Jesse. Just a few things that he handled. A red plastic kazoo from one of his birthday parties; arcade tokens, from the day she took him to Coney Island. She remembers him standing before a machine, oversize mallet in hand, pounding down cartoon totems as they popped up through holes; remembers thinking that he looked exactly like a tiny wrathful god.

Seeing all this stuff delivers a whomp, straight to her chest, just as she feared. She tries to ignore it, tries to remain focused on the problem at hand—the rift in her Goddamn kitchen—instead of the larger, more amorphous problem of how to reconcile herself to every fucking thing in her fucked-up past. She fumbles with the bag, gets it open, gets the kazoo in her hand, holds it aloft with something like a gesture of triumph.

“That?” Victor says.

“This,” Ollie says.

“Not exactly the first thing one thinks of when thinking of a magical instrument.”

“Trust me,” Ollie says.

“Why the fuck not,” Victor says, and he reaches out to take it. She almost hands it off but then she hesitates; something about the idea of Victor playing Jesse’s kazoo bothers her. If anybody is going to use it for a magical purpose it should be her.

“I got this,” she says.

She puts the kazoo between her lips and blows.

A forgotten force moves from her belly up to her head, out through her face. She projects herself out into the air and tangles with the impossible shape of the rift. Everything that’s happening is invisible and intangible but it reminds her of physical grappling. Wrestling; rough fucking. The application of force and the response to force. It reminds her of Ulysses and it reminds her of Donald. And—she has to admit—it feels good. Scary good.

She sucks breath and then buzzes on the kazoo again. It shrieks. The rift quivers. Victor starts jangling the string of bells finally but that doesn’t really matter; he’s not a factor in this ritual anymore, if he ever was. He’s like someone who’s been nudged out of a threesome: it’s all between her and the rift now.

She concentrates; she frowns. She can sense the many ways in which the rift is trying to fight her but she knows just as many ways to smack it back into behaving. She knows exactly what she’s doing.

And the moment that she knows that, with certainty, it’s over. She’s won: the rift collapses down into a single delicate tendril of smoke. She steps forward and whiffs it away with her hand.

“Jesus fuck,” Victor says.

“How about we not do that again,” Ollie says, breathing hard.

“Yeah, OK,” Victor says.

“OK,” Ollie says. Except. Except there’s a part of her that’s still exhilarating from the experience, like a kid who just got off a roller coaster, and all that part wants is to do it again and do it again right now. That part of her is already calculating how it could be done better, how next time she could control the experience more effectively, maybe by using the right tool at the outset instead of bringing it in later—

She looks down at the kazoo, to see if it could serve this purpose, but then she sees that the ritual took something out of it. It’s been desaturated somehow, its red gone grayish. She bends it gently between her fingers to test its plasticity and it crumbles like an old rubber band.

Nothing comes without its cost, one of the oldest rules there is. But she can’t say it doesn’t hurt, to have one more piece of the past disappear like that.

She looks up, her exhilaration forgotten, and she considers holding Victor accountable for this loss, thinks about confronting him with the pieces of the kazoo, waving them in his face. It would feel good to have someone to blame, to be able to convert the sadness to anger. But, stung and sad, she can’t muster up the feeling that there would be any point. So she stands there, still, while Victor paces around the kitchen for a minute, looking jumpy as hell.

Finally he glances into the sink. “Ew,” he says. “What are we going to do with this?”

Oh yeah: that severed worm. “Do you think it’s wrong to just throw it in the garbage?” Ollie says, after thinking about it for a second.

“I don’t know. It feels wrong. Maybe. Yes.”

“You think it’s dangerous?” Ollie asks. “I mean—it’s, what, it’s an interdimensional monster. It seems like maybe that’s dangerous.”

“It’s dead,” Victor says.

“Right, but—f

or all we know it could be doing harm just by being here, as a thing that fundamentally doesn’t belong in this world? Like, is this thing doing damage to the fabric of reality by being here, in our kitchen?”

“No? Hopefully not?”

“I’m just saying,” Ollie says, “it seems wrong to just throw it in the garbage unless we’re sure.”

“I don’t know how we can be sure.”

“Maybe we can—keep an eye on it for a while.”

“What, just leave it there in the sink?”

“I don’t know, Victor, I’m just trying to—”

“Wait a second.”

Victor rummages around in the cabinet under the sink and finds a paper lunch-bag, flaps it open. With his other hand he gets the tongs and lifts the two pieces of worm, drops them in the bag one at a time. One corner grows a little sodden, from leakage. He rolls the bag closed and opens the freezer.

“Really?” Ollie says. “No.”

“Do you have a better idea?”

“I’m not saying I have a better idea. I’m just saying I don’t like the idea of there being a dead thing in our freezer.”

“Have you looked in our freezer lately?” Victor says. “ ’Cause it looks like fucking Pat LaFrieda’s Meat Purveyors in there.”

“A dead thing that isn’t food, I mean.”

Victor shrugs. “I owned a snake when I was a teenager,” he says. “Used to feed it mice. You know where you store dead mice?” He nods at the freezer.

“OK, fine,” Ollie says. She bites her lip uneasily as he packs it in there. “I just want to go on record as saying that there was almost certainly some better solution.”

“The only other thing I could think of was to cook it and eat it,” Victor says, wrinkling up his nose a little.

“Right,” Ollie says. “ ’Cause there’s no way that that could have been a total disaster.”

“Hey,” Victor says, “for all we know it could be delicious. Char-grill it, hit it with some unagi sauce, serve over rice? Yummy.”

The Weirdness

The Weirdness The Insides

The Insides